More news

- Focus on industrial: Powering the energy industry during extreme heat

- Focus on powder coatings: The coatings industry’s transition to PFAS/PTFE-free solut...

- “We see sustainability as a purpose, as a reason for doing business” – P...

- Focus on industrial: High-performance coating protects tanks at biopolymer production plan...

- Focus on powder coatings: Novel high-speed crosslinking technology

When you think of an octopus, you might be envious of its eight limbs. But scientists are a bit more interested in something else: its skin. Cephalopods — like octopi and squid — change colours rapidly in response to threats or even just changes in light thanks to xanthommatin, a naturally occurring dye present in their bodies. Researchers at Northeastern University’s Kostas Research Institute work with a synthesised version of this dye, experimenting to create colourants that change in response to different stimuli. Their latest discovery: using this to create paint that can change colours when exposed to light

This story has been republished with permission of Northeastern Global News.

KRI focuses its work on interesting components from natural materials, Cassandra Martin, a research scientist at the institute, said, looking into ways those components can be replicated and used in the real world. Cephalopods have been a starting point due to the unique nature of their skin.

“Their colour change is so rapid and it’s so vibrant and it’s so intense,” Martin said. “There’s not a lot of natural systems out there that change that fast and there’s not a lot of colour-changing materials that are that fast without requiring a lot of external (changes).”

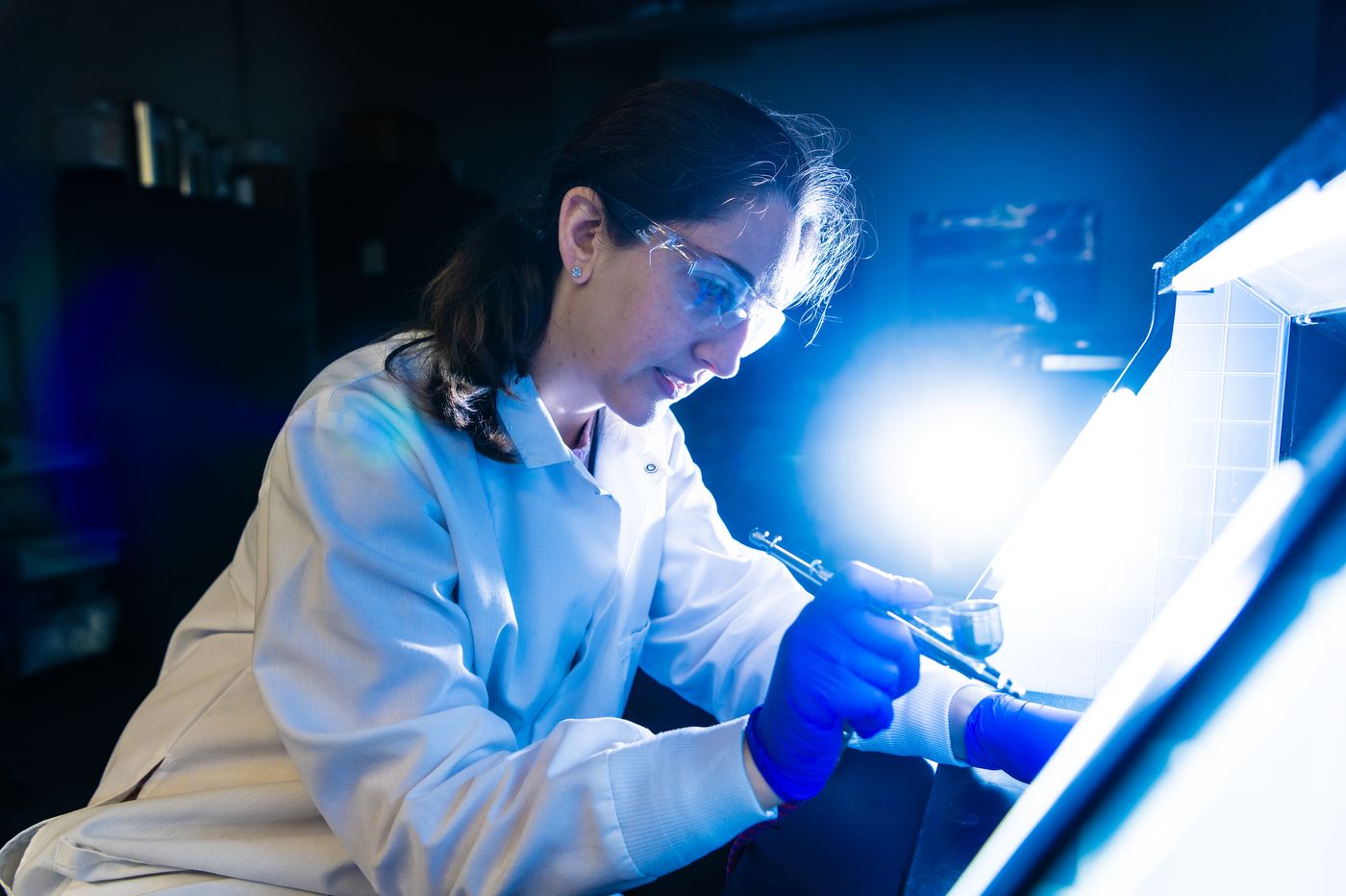

The staff at KRI has long worked to replicate this. Previously, the lab used this to create wearable patches that change colour when the wearer gets too much sun. Dan Wilson, senior research scientist at the Kostas Research Institute, said the team wanted to try to find a way to make a material where this change could be reversed to return the material back to its original colour.

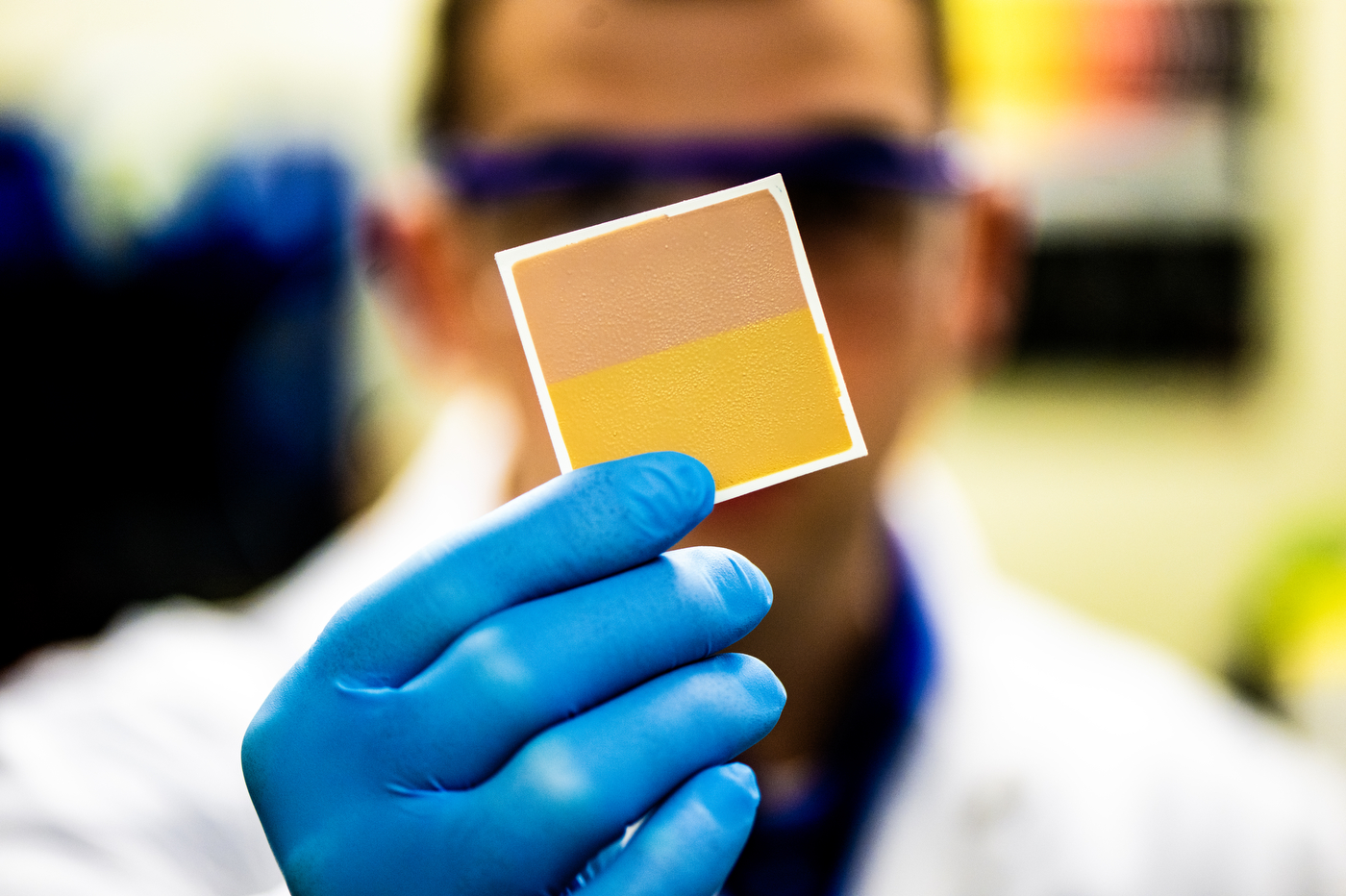

Last summer, Kaitlyn Flynn, then an intern/visiting student, was working on a project using this colourant and decided to further research how to do this. She and the team found that titanium dioxide served as a conductor for the colour change. Mixing different amounts with the xanthommatin could speed up the change or add to the intensity of the colour shift.

The changes can happen in as quickly as five minutes and can last as long as 24 hours, depending on how long the paint is exposed to light. The colourant can easily be made in as little as two hours and added to water or oil-based paints.

The research ended up being published recently in Advanced Science.

READ MORE:

Protecting fine art: Coatings specialists work with galleries and museums

“We’ve imagined a scenario where if you want to have art that changes from day to day on an interior wall, like maybe in a coffee shop or something you could use a regular projector to project a pattern onto the wall, temporarily paint in this colour and this pattern or this art, and then over time that fades away and you can redo it again, ideally as many times as you want,” Wilson said. “We can create temporary artwork or art or paint that could potentially track the weather or track the environment that it’s in.”

Besides the ability to create temporary art, this discovery has environmental implications. It can serve as an eco-friendly alternative to paints currently on the market.

“Paints that are like commercially used nowadays can have harmful chemicals in them, so they can have things that can be harmful to the people that are painting them,” said Flynn who is now getting her PhD. in chemistry at Northeastern. “The fumes can be super harmful. They can be harmful long term if you’re exposed to them for a long time. They can also leach out into the environment. Searching for a more natural way to make these paints creates a safer environment for the people using it and for the people that are going to be exposed to it.”

Moving forward, Flynn and Martin said they hope they can apply this system to other materials and expand beyond the yellow-red colour palette they used in the initial experiment. They also hope to get to the point where the user can decide how quickly they want the colours to change on the paint.

Erin Kayata is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email her at e.kayata@northeastern.edu